In this workshop, we encourage people of all genders to partake in this ancient ritual. We also encourage participants to engage in a text study which examines the often gendered language of the tefillin ritual, as well as the marital and sexual imagery used in the tefillin blessing. The text study investigates both the spiritual significance of tefillin as well as their connection with masculine privilege.

By JP Payne

Please note that language used to describe the LGBTQ community and our experiences has rapidly evolved as LGBTQ lives and experiences have gained more visibility. This resource may contain language/content that is now considered outdated and/or offensive by some. For a list of affirming terms related to LGBTQ inclusion, check out Keshet’s LGBTQ Terminology Sheet in the Resource Library.

We believe in the importance of showing growth and progress within our community so we have left the resources on our page to do just that. If you have questions, please contact us at [email protected].

The act of laying tefillin is an act of intimacy between a Jewish person and God. In this workshop, we encourage people of all genders to partake in this ancient ritual. We also encourage participants to engage in a text study which examines the often gendered language of the tefillin ritual, as well as the marital and sexual imagery used in the tefillin blessing. The text study investigates both the spiritual significance of tefillin as well as their connection with masculine privilege.

Number of Participants: 10 – 20 participants

Time needed: 2-‐3 hours

Time needed: 2-‐3 hours

Different styles of tefillin exist: Ashkenazi, Sephardi, right-‐handed, and left-‐handed, to name a few. The most common set of tefillin will be Ashkenazi-‐style right-‐handed tefillin. Use what is available, but be aware that some participants may be familiar with different styles.

Laying tefillin requires the use of both hands and some range of motion for both arms. For group members for whom this would be difficult, please consult a rabbi on a method of laying tefillin that will work for them.

Plan the workshop to occur during daylight hours, as tefillin are worn in daylight.

Tefillin are not worn on Jewish holidays. Please check with a reliable Jewish calendar or a rabbi if you are unsure which days are considered holidays.

Adjustments can be made to the tefillin shel rosh (head tefillin) to fit a participant with the consent of the owner. If you cannot adjust the tefillin, anticipate that some people may have poorly fitting tefillin. This is acceptable for the purposes of a learning workshop.

These two passages are interpreted as commandments to lay tefillin. What are tefillin reminders of according to Exodus? What are they reminders of according to Deuteronomy? How do you see the tension between liberation and bondage in these texts?

Two significant community events in the Torah are the Israelites’ exodus from slavery in Egypt and God’s revelation at Sinai. Who participated in these events?

Why might women be exempt from time-‐bound commandments in the times of the Talmud? Why might women remain obligated for time-‐independent commandments?

Why would women not be exempt from commandments which are time-‐independent? How do you interpret the word “exempt” in light of the second passage?

What might the reasoning be behind the Talmud’s statement that a deed is greater if it is obligatory rather than voluntary? Has this proven true in your own experiences? Has this proven untrue in your own experiences?

Why does Roth oppose creating a new law (takkanah) which would obligate women to lay tefillin?

Why does Friedman find not obligating women to lay tefillin problematic?

The tension here is between egalitarianism and tradition. Do you feel this tension in your own life? Do you experience other tensions between tradition/ritual and values/ethics?

What are God’s tefillin a reminder of? What does it mean for God to participate in the marriage/bondage imagery of tefillin?

How does the concept of a tefillin-‐laying God affect the power dynamics between God and people?

Alterations of the flesh engage the spirit. Fasting, cleansing/immersion (as in a mikvah) and binding (as with t’fillen) are more familiar Jewish physical vehicles for intense psychological shifts, into a mental state that could be designated sacred. Cutting or piercing, in a sexual or S/M context, have a similar effect, and therefore require (for me) a certain level of trust and connection.

-‐-‐Micah Bazant, 1999

How do physical rituals (or “alterations of flesh”) produce spiritual or psychological transformations?

What kind of trust is needed for sex? What kind of trust is needed to lay tefillin? How does one develop this trust?

After 5000 years of persecution, you’d think we’d be sick of it: name-‐calling, whips and chains, submitting to dominance. We Jews ought to be pretty over that whole scene by now. And we are—until it comes to the bedroom door. …

Madame Alexia, a professional dominatrix … takes a green light from the fact that that nearly half her clients are Jewish as well, and is pleased to note that they range from wholly unobservant to “full-‐on guys with beards and black hats” … [she] believes that BDSM is not only A-‐OK in the Jewish tradition—it’s consistent with it. This confirmation comes virtually in

absence of an official ruling. There’s nothing in Jewish religious texts that either condemns or condones sadomasochistic behavior. But Alexia points out the bondage-‐like imagery of laying t’fillin and the self-‐flagellation that accompanies the Yom Kippur service—both of which, to her, contain echoes of sadomasochistic behavior. … Alexia notes that, “In the Torah, no one tries to pretend that they’re not terrified of God. There’s this constant threat of punishment and wrath, but the Israelites don’t mind—it’s like that’s what they love about God.”

According to Dr. Ken Stone, Associate Professor of the Hebrew Bible at the Chicago Theological Seminary, Alexia and her clients are in some pretty good company. In a recent paper, Dr. Stone argues that there’s quite a bit of sadomasochism in the Holy Books—particularly in Jeremiah, where the prophet describes his relationship to God in terms that resemble a dominant/submissive sexual dynamic: “O Lord, you have enticed me, and I was enticed; you have overpowered me, and you have prevailed.” Dr. Stone argues that the worshipful attitude Jeremiah takes towards God is in line with a voluntary sexual submissive—someone who derived sexual or spiritual pleasure from the domination imposed on him by God.

Do you agree with the author that the threat of punishment and wrath is what the Israelites of the Torah loved about God? What about modern people?

What “spiritual pleasure” is derived by the interplay of submission/domination?

by Elizabeth Tikvah Sarah, published in The Torah: A Woman’s Commentary

I cannot bind myself to You

I can only unbind myself continually and free

Your spirit within me

So why

this tender-‐cruel parody of bondage

black leather straps skin

gut and

sacred litany of power and submission which bind us

Your slave-‐people

still?

My own answer is wound around with every

taut

binding and unbinding

blood rushing heart pounding life-‐force surging

pushing panting straining struggling to break through to You

How are tefillin a “tender-‐cruel” parody of bondage?

The poet calls us God’s “slave-‐people still.” What is the first slavery she is referring to? What slavery are we in now? What is the significance of the question mark at the end of this line?

What is the poet’s “own answer” alluded to in the last stanza? What actions does she describe as part of her own answer?

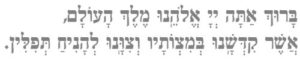

Baruch ata Adonai elohanynu melech ha’olam asher kidshanu b’mitzvotav vetzivanu lehani’ach tefillin.

Praised are you, Adonai our G-d, Sovereign of the Universe, who has made us holy with the mitzvot and instructed us to wear tefillin.

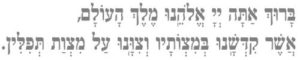

Baruch ata Adonai elohanynu melech ha’olam asher kidshanu b’mitzvotav vetzivanu al mitzvat tefillin.

Praised are you, Adonai our G-d, Sovereign of the Universe, who has made us holy with the commandments and instructed us about the mitzvah of tefillin.

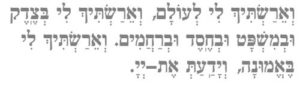

Ve’ayrastich lee l’olam

ve’ayrastich lee betzedek u’mishpat u’vchesed u’vrachamin

ve’ayrastich lee be’emunah

veyada’at et Adonai.

I will betroth you to Me forever. I will betroth you to Me with righteousness, with justice, with kindness, and with compassion. I will betroth you to Me with faithfulness, and you shall know G-d.