By Amanda Borschel-Dan

First-grader Eli loves to dress up as Queen Esther for Purim. A real girlie-girl with shoulder- length brown hair and a mischievous smile, when her sisters, 9 and 5, aren’t looking she may “borrow” their accessories. Pretty typical stuff for a seven-year-old Californian girl.

Except Eli was born a boy.

“For us, in the beginning when two years ago she said I want to wear girls’ clothes, we thought it was a phase — even hoped it was a phase — when we weren’t as educated on gender issues,” said mother Jodi in conversation with The Times of Israel.

At the time, Eli was in pre-school at a Bay Area Jewish Community Center near the family’s home. When Eli persisted in wanting to dress as a girl, however, Jodi and her husband consulted with the JCC director and Eli’s teachers. They were told to roll with her requests, otherwise they may “squash her identity, which is not good for her sense of self.” It’s a critical time in Eli’s development, they were told, and it’s best to support her in being who she is.

Two years on, ahead of first grade, Eli’s family reached out to the community’s Jewish day school for help in creating a supportive school atmosphere. The school turned to Keshet, an advocacy and education organization which works toward “the full equality and inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender Jews in Jewish life.”

The school’s principal wrote a letter to parents stating, “I trust that as we have embraced Eli’s gender expansiveness as a community to date, we will continue to embrace her identity moving forward,” and brought in Keshet experts to train faculty. The entire staff showed up, said Jodi, who reported Eli hasn’t experienced any bullying at school, or actually pretty much anywhere else in the family’s very Jewish community-centric life.

“I think it’s great that Eli walks around as this confident kid, really secure in who she is. A lot has to do with the support from the community and friends,” said Jodi.

The family lives in Northern California where the idea of having a transgender child is increasingly accepted. In March, Jewish media highlighted the case of 13-year-old Tom Sosnik who was supported by his community during a high-profile bar mitzvah-esque renaming ceremony. Jodi mentioned there have been other similar ceremonies in the Bay Area in the recent past.

“In the Jewish community, as there are increasing rates of social acceptance, more and more young people are coming out and coming out earlier,” said Joanna Ware, a regional director at Keshet. Ware said, however, there is very little reliable data on the rate of transgender identity in the general or Jewish population because there is “still so much stigma.”

Parents commonly call Keshet with questions about gender or sexual issues surrounding older children in transition, such as what to do during summer camp. But, Ware said, Keshet is increasingly working with parents and teachers in cases of children as young as three or four.

“We get a lot of requests from people with children in preschool,” she said. “They’re not calling saying ‘I have a trans kid.’ They’re saying ‘I have a gender nonconforming kid’” and asking for resources and support.

Jodi and Eli’s whole family is in counseling and consultation with foremost transgender specialists in the Bay area. They’ve had discussions regarding hormone blockers and other medical interventions that may lie in the distant future, but Jodi said she and her husband are taking things one day at a time.

“Like every parent, I don’t want life to be difficult for my child. I see how sure Eli is of herself, how happy she is [as a girl]. All we want for our child is to be happy and healthy — and Eli is both of those things,” said Jodi.

Like every parent, Jodi cares for her child’s future. But as the parent of a presumably transgender child, a black cloud of grim statistics looms overhead.

According to a 2011 survey of more than 6,400 trans people by the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National LGBTQ Task Force, more than 41 percent of the transgendered polled had attempted suicide, versus 1.6% of the general US population.

Over 90% reported harassment or discrimination at work, and compared with the general US population, the transgendered are four times more likely to live in poverty and twice as likely to be unemployed.

However, a 2014 Dutch study, “Young Adult Psychological Outcome After Puberty Suppressionand Gender Reassignment,” published in the medical journal Pediatrics showed much lower rates of anti-social behavior in the 55 tracked Dutch transgendered who began their transitions in their teens with puberty blockers.

The breakthrough study found that after a protocol following the international Standards of Care with a team of mental health experts, physicians and surgeons, the studied individuals’ well-being “was similar to or better than same-age young adults from the general population.”

But is society ripe for mainstreaming a teen transgender population?

Former Olympic athlete Bruce Jenner and patriarch of the Kardashian television clan will give a two-hour interview to Diane Sawyer airing on Friday, April 24. (Photo by Mark Von Holden/Invision/AP, File)

In the past few years, the trans community has gained widespread acceptance into popular culture, with transgender story lines or trans stars in popular Hollywood television series, including the critically acclaimed Jewish-themed “Transparent.” International headlines proclaimed this week that a ripped transgender male is leading the cover model contest for Men’s Health magazine.

But most popular media discussion surrounds former Olympian Bruce Jenner and his impending announcement on ABC’s 20/20 with Diane Sawyer this Friday.

For Judaism, all this talk of transgender is old hat.

In rabbinic literature, Judaism has held an ongoing 2,000-year conversation on the subject of gender, and terminology for the transgendered appears hundreds of times in the Midrash, Mishnah and Talmud. Even the biblical creation of the world could be interpreted through a transgender lens.

And so to understand Judaism’s relationship with the transgendered, we must begin in the beginning.

In the midrash Bereshit Rabba, a biblical expositive text on the book of Genesis redacted around the 5th century CE, Rabbi Yirmiya Ben Lazar said that at the time God created the first man, He created him “androgynous.” As stated in Genesis 1:27, “God created him in His image, in the image of God he created him, male and female he created them.”

The midrash continues that according to Rabbi Shmuel Bar Nachman, when God create the first man, “He created him with two faces and sawed them apart, and made them with two backs here, and two backs there.”

The first openly transgender person ordained by the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College, Rabbi Elliot Kukla, has written extensively on the overlap of Judaism with transgender issues on the TransTorah website.

Rabbi Elliot Kukla. (photo credit: Nic Coury)

There, Kukla describes terminology used in rabbinic literature, such as the Greek androgynos cited in Bereshit Rabba, where it’s defined as a person who has both “male” and “female” sexual characteristics. Kukla wrote he counted 149 references in the Mishnah and Talmud (redacted in the 1st-8th centuries CE), and 350 in classical midrash and Jewish law codes (written between the 2nd and 16th centuries CE).

Kukla also discusses the term tumtum or a person with indeterminate or covered sexual characteristics, which has 181 references in the Mishnah and Talmud, and 335 in classical midrash and Jewish law codes. He defines “aylonit” as one who is identified as female at birth but who develops male characteristics at puberty and is infertile. It has 80 references in the Mishnah and Talmud and 40 in classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

And then there is the “saris,” who is identified as male at birth but develops female characteristics at puberty or is lacking a penis. Kukla qualified that a saris can be “naturally a saris” (saris hamah), or become one through human intervention (saris adam). He counted 156 references in the Mishnah and Talmud and 379 in classical midrash and Jewish law codes.

There are, then, hundreds of references, but trans-male Rabbi Becky Silverstein said in conversation with The Times of Israel that he was ambivalent about rabbinic literature’s discussions of gender.

“I was excited the rabbis were talking about androgynos, and tumtum, was excited that they were looking at gender in that way,” he said of his initial discovery of these terms. “But we understand gender and sex differently than the rabbis did in some ways, and I’m not sure… Are they commenting on what’s actually going on in their lives or having this total intellectual discourse?”

Rabbi Becky Silverstein serves at a Conservative synagogue in California. (Jordyn Rozensky)

He said he and other trans Jews “find it useful at least to say the rabbis are talking about it,” and added that the rabbis had many more categories of gender than are used today.

In the US, “gender binary is so strictly reinforced, which is also true in the Jewish world,” said Silverstein.

Silverstein has a long history of pushing gender binaries. Born female, Silverstein came out as a lesbian in December 2000 after his first semester in college.

“People would have called me butch,” he said in retrospect, adding that in six years he wore a dress maybe twice, and was an athlete on the crew team.

He began rabbinical school at the nondenominational Hebrew College in 2008, where he started “thinking about gender more and trying to figure out what that meant. I started learning this language of gender and gender identity,” he said.

Halfway through rabbinical school he came out as “gender queer” — “an identity that is neither male nor female, that is outside, in between, and around the binary,” said Silverstein.

For Silverstein, and many who spoke with The Times of Israel, gender is a fluid concept, and eventually he felt himself more masculine and came out as male. Silverstein has not yet sought medical intervention in his transition.

“I haven’t changed my name, but use male pronouns and place myself somewhere outside of the binary,” said Silverstein, who works with youth in his position at a Conservative synagogue in California.

Golden Globes best actor Jeffrey Tambor as Maura in ‘Transparent.’ (courtesy Amazon Studios)

As a rabbi, Silverstein said he grapples with the intersection of Judaism and gender. “I’m a trans guy. How does halacha [Jewish law] apply to my life?” he asked.

Most streams of progressive Judaism accept and welcome the transgender community with open arms. There are a growing number of transgender rabbis who are spearheading the creation of new and innovative rituals, or the changing of existing liturgy to reflect more inclusive language.

But the question of halacha vis-a-vis the Orthodox transgender community is much more complicated, and often fraught with emotional turmoil.

“The cultural matrix of Orthodox Judaism differs greatly from Liberal Jewish society. In the latter, intense interest and investment in personal identity choice is often a source for public celebration (a la conversion, which is not generally publicly celebrated by the Orthodox),” explained Rabbi Daniel Landes, a student of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, the towering figure of 20th century Modern Orthodoxy.

Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies director Rabbi Daniel Landes. (photo credit: courtesy)

“Orthodox understanding accepts identity as it is, and one should get on with doing mitzvot and avoiding sin,” said Landes, the director of Jerusalem’s Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies.

Empathic with the plight of religious transgender community, however, Landes said, “The situation of transgender youth is not necessarily one of emotional imbalance or loose experimentation, as many of my Orthodox colleagues fear — sometimes correctly. It is often that somehow the gendered self and the body has been misfitted. This tragic, tortuous circumstance won’t be changed by repressive therapies or pious pronouncements. We need to allow and to guide — carefully! — people to return to their actual selves. And such people deserve to live full and participatory lives in our community.”

But for many, if not most, in the transgender community, surgery and cross-gender hormones are an integral part of their transition. These steps, said Landes in a lengthy responsum email, present serious halachic problems, including “the prohibition ofsirus — castration/sterilization, which is a Biblical prohibition for men (Leviticus 22:24) and at least a Rabbinic prohibition for women (Even HaEzer 5:11). Authorities understand the forbidding of cross-dressing (Deuteronomy 22:5) as including any procedure (including hormonal treatments) that leads to the appearance of another gender. Bodily mutilation is one of the other difficult issues.”

Additionally, asked whether a sex change operation would halachically change gender status, he answered, “Overwhelmingly, Orthodox authorities are in the negative.”

“A man with artificial breasts, a plastic vagina and whose penis has been removed remains chromosomally and halachically a man. The same inverse status conservation is also true for a woman,” said Landes.

However, Landes cited an independent opinion from Rabbi Eliezer Yehudah Waldenberg (1915- 2006), who was the preeminent halachic medical expert at Jerusalem’s Shaare Zedek Hospital.

“In several responsa (Tzitz Eliezer) he widens the discussion to include other, mostly 19th century voices. The assumption is that such situations do exist, so to speak, in the ‘finest families’ (my term), and that post-op, gender change is effective to such a degree that a man changed to a woman does not even need to grant his wife a [decree of divorce] get (a very serious halachic issue) in that ‘he’ no longer exists, as a man. Indeed, Rabbi Waldenberg seems to imply that this new woman could be married to a man,” said Landes.

Jewish educator Yiscah Smith in Jerusalem on

Thursday, January 15, 2015. (photo credit: AP/Dan Balilty)

Jewish educator Yiscah Smith opened her memoir, “Forty Years in the Wilderness: My Journey to Authentic Living,” in describing herself as a five-year-old boy who already felt he should have been born a girl. She looked to the Tzitz Eliezer for guidance in her transition from male to female as a religious Jew.

Smith’s journey to womanhood included becoming an ultra-Orthodox Chabad husband and fathering six children, leaving the faith and trying on a homosexual lifestyle, and eventually realizing she could physically become the woman she felt destined to be.

A decade ago at age 54, Smith finished her four-year medical transition with the surgery that aligned her body with her female identity.

For Smith, and for many who transitioned as adults, the teenage years were the hardest as her body was increasingly “betraying” her and becoming more and more male while her inner identity was distinctly not.

“I hated my teenage years. Every morning I would wake up and wish I wasn’t alive — not suicidal — but the way I woke up was not reality. I needed alignment, harmony,” she said in conversation with The Times of Israel.

Smith agreed that every teen suffers to a greater or lesser extent.

“But what most people suffer is not living an inauthentic life” as transgender teens do. This is compounded, she said, “as the body takes on a more definite gender assigned from birth.” For her, there was a feeling then that “wow, my body really is lying to me,” she said.

Although she believes in a lengthy, soul-searching process, stories such as eighth-grader Tom Sosnik’s much-publicized coming out ceremony make her feel “humbled by how quickly times are changing.”

“When I was his age, this wasn’t in my vocabulary, it wasn’t a wish or a prayer,” she said, and added she feels like his “third Jewish grandmother.”

“When the unimaginable becomes reality we are living in an era of redemption,” she said.

Are parents today merely caving in to their children’s demands in seriously entertaining the possibility of a transgender identity? This is perhaps a natural question as children such as seven-year-old Eli have begun their transitions at increasingly earlier ages.

A Jewish mother from America’s Midwest whose child “R” is currently transitioning responded to The Times of Israel in an email interview.

“This seems like a general critique of American parenting, which in some ways I agree with. But your question here is not has R been allowed too many choices: to eat candy or play video games… Here we’re talking about something very different. There are choices of indulgence… candy, play, games. There are also choices that we can make that are affirmations,” she wrote.

R is in his last year of high school.

“Prior to R coming out, I’d read many stories of trans kids and how their parents supported them. I always found those very beautiful and nurturing choices that the families made together. I can only hope that by choosing to affirm R’s choice and to allow him to be the person he feels he is we are doing the same,” she wrote.

Dr. Norman Spack’s patient Nicole (left), next to her identical twin brother. (YouTube screenshot)

A proliferation of transgender coming-out stories shows a marked difference in societal norms. And increasing numbers of parents are raising their children with much broader gender roles and with greater diversity, said Arlene Lev, the founder and project director of the State University of New York at Albany’s Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Project.

“Generally speaking, parents are doing the best for their kids,” said Lev, a family therapist at Choices Counseling and Consulting. “They’re trying the best they can to balance — for shlom bayit — to give their children values and also listen to them.

The situations are not always so clear cut, however.

“Although a parent’s job is to set rules to guild children, when it comes to gender identity and expression, it is best to listen to children’s emerging identities,” said Lev.

Sometimes it’s best for parents to just allow their child space and time.

“I think all children to some extent, if they’re allowed to explore gender, explore the meaning and find themselves,” she said.

Pediatric endocrinologist Dr. Norman Spack is one of the founders of the Gender Management Services Clinic at Children’s Hospital Boston in 2007. Spack, the country’s pioneer in treating transgendered teens, has seen a sharp uptick of cases in the past decade, which he attributed to popular society’s growing ease with the gay community, and by extension, the transgendered.

“It’s a generational thing,” said Spack, who credited a 2007 Barbara Walters special with helping to bring the issue to America’s consciousness.

An initial major motivator for Spack to begin his work with transgendered youth was early exposure in the mid-1970s to the homeless in his hometown of Boston. Many had been thrown out of their houses because of their gender identities. Spack saw a disproportionate rate of suicides among the Boston community, and in the broader untreated transgender community, which has the highest rate of suicide in the world.

“Nowhere in the Torah is a human a healer,” said the Jewish Spack to The Times of Israel. But while taking a course on the Rambam, a physician in addition to being one of the foremost rabbinic scholars of all time, Spack saw a biblical imperative to aid this community through his work in the Leviticus verse, “Do not stand idly by while your neighbor’s blood is shed.”

A popular YouTube star, 16-year-old transgender teen Taylor Alesana, committed suicide on April 2, 2015. (Facebook)

Israeli psychologist and Gender Studies professor Tova Hartman described the stress likely felt by transgender teens upon realizing, “I’m not belonging and am beginning to feel something is off.”

“That kind of knowledge without knowing involves so much suffering,” said Hartman, the dean of Humanities at Ono Academic College. She advocated allowing people the space to “move in and out of environments and identities, and try things that aren’t dangerous or harmful.”

Spack told The Times of Israel that when he opened the clinic, about 11% of his patients had tried suicide. “Nobody has tried after they walked through our door,” Spack said. Even though the patients may have not yet been treated, the availability of treatment is, amazingly, enough to bring vast relief.

“When going forward is indeed the correct decision, you will usually see the teen blossom, both academically and socially, in a most gratifying way,” affirmed Dr. Sandra Samons, a clinician with a doctorate in human sexuality who has treated transgender clients since the early 1990s.

Samons said there are several factors which need to be taken into account when deciding on a “course of action or inaction,” including an early and persistent history of transgender expression and “how they respond to being out about their transgender identity.”

“It involves a case by case evaluation of whether more harm may be done by helping the teen in going forward or by holding the teenager back by denying emotional and medical support,” said Samons.

Spack’s was the first clinic in the US in which teens were medically treated “to help them into the sex they affirm,” he said. However, before he administers any type of medicinal therapy, the teens are “tested in every possible way” to discern if their distress is indeed due to gender dysphasia.

Typical medical intervention, explained Spack, begins at the onset of physical puberty, when puberty blockers are given. These blockers, which can be stopped at any time with no lasting effects, are the medical equivalent of “hitting the pause button.” They allow the child to continue to explore his inner world and grow into his identity, before making lasting physical or hormonal changes.

In males, the puberty blockers prevent the development of an Adam’s apple, or masculine- looking hands and feet, and height. For females, they prevent menstruation and the development of breasts.

In the late teens, if the patient’s team agrees it is time to proceed, cross-hormonal therapy may be administered. The teen will begin to physically look more like the gender with which he identifies, and some of the effects are irreversible, said Spack, such as voice pitch.

When administering cross-hormonal therapy to born females, Spack strongly advises a complete removal of all female sex organs due to the hormones’ carcinogenic side effects. This obviously renders the patient irrevocably sterile.

‘A voice like Minnie Mouse and the face to match’

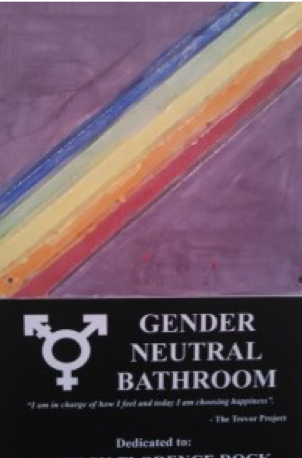

Midwestern Jewish teen “R” is set to enter a college in the fall where all the bathrooms are gender neutral. There are already transgender students living on this campus, he said.

A plaque identifying the new gender-neutral bathroom at Jack

M. Barrack Hebrew Academy near Philadelphia. (JTA)

“It sounds like heaven, and I can’t wait to be in a place where I can be myself without worrying about a negative or violent response from the community around me.”

R hopes to begin taking testosterone within the next year.

“I’m five foot four inches tall, with a voice like Minnie Mouse and the face to match. I don’t pass in public, and I don’t feel comfortable in my own body,” R wrote. He said that when people find out he is trans, they always ask, “So what about surgery?”

“For me, that’s a hard question. I know I want top surgery, because my breasts are one of the largest sources of my dysphoria, but the idea of bottom surgery makes me pretty uncomfortable,” he said.

Michigan surgeon Dr. William Kuzon said the norm is to wait until age 18 for any surgery. He told The Times of Israel that whereas with the male to female operation there are very good surgical options, the female to male “can be very troublesome” and in creating a phallus there can be “huge complications.”

R, like many trans males, may elect not to undergo phalloplasty surgery.

“I don’t know how I feel about a body part being added to me. That being said, I don’t think any kind of surgery is in the cards for a couple of more years. I want to get used to the body that testosterone would give me before I go about making more changes,” he said.

R is out to several friends at school and from Jewish summer camp, and also to several people in his Jewish community.

“Everyone has been very supportive. I feel that every time R takes the step of coming out it’s a step forward for him in owning and inhabiting his identity; making him feel more comfortable in his skin,” wrote his mother.

R said being Jewish has played a role in his identity.

“I think the best example of this is the Jewish definition of masculinity. Throughout the Torah the most famous men are not the ones with the strength of ten men and gleaming abs. They’re the smart ones, the thinkers, the nerds. This trend is also evident in the synagogue that I’ve grown up going to, and even presents itself in my father,” he wrote.

“For a trans guy like myself, I think that makes me able to feel a lot better about myself as a man, because realistically, I’m never going to look like the male sex symbol that our modern world loves.”

R’s mother said that while his original announcement came as a surprise, she and her husband are trying to be supportive while getting input from the experts.

“For me, the announcement was one that gave me hope that this might be a path out of the dark and self-destructive places he’s been for the last two years. For me, if finding a trans- identity helps R live a happy and productive life, hallelujah!”

She said there are times when she does a double take and wonders where her daughter went.

“But I realize that’s a superficial reaction. The same soul is there, just in different clothes. The child I gave birth to is still right here with me. Things are different but they’re not.

“And after all the worry that my child might kill himself, to see R happy and vibrant in this new identity is a gift,” said R’s mother.