By Dana Rudolph

The Jewish High Holiday season begins this week, so let’s take a look at some new stories that feature queer, Jewish families, including a children’s picture book and a grown-up memoir by a woman with four lesbian moms.

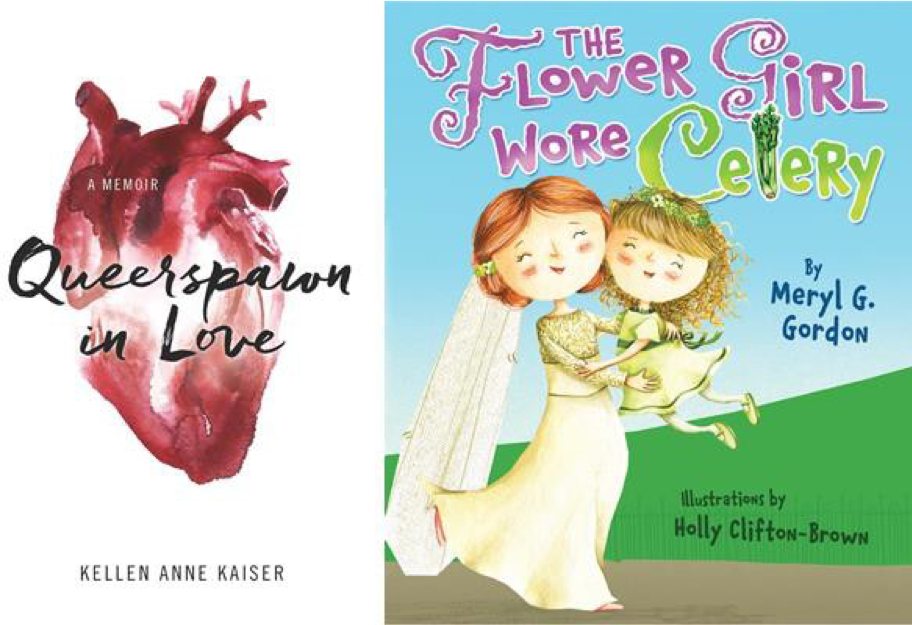

Meryl Gordon’s The Flower Girl Wore Celery is one of two children’s books to gain publication through a writing contest hosted by Keshet, the national organization for LGBTQ Jews, in partnership with Kar-Ben Publishing. (The other title, The Purim Superhero, came out in 2013.)

Gordon’s book, with dynamic, whimsical illustrations by Holly Clifton-Brown, tells the story of young Emma, who is asked to be the flower girl at her cousin Hannah’s wedding. Emma is excited, but has some misconceptions. She thinks she will dress as a flower—until her mother tells her she’ll wear a “celery dress” like the bridesmaids. She then imagines a dress covered with stalks of celery. When she hears there will be a “ring bearer,” she envisions a furry “ring bear.” About Alex, to whom her cousin is engaged, she knows nothing.

She is surprised to learn that celery refers to the dress color; that the ring bearer is a human boy; and that Alex is a woman. “No celery. No bear. And two brides! Nothing was what she had imagined,” she thinks—but takes it all in stride. Gordon doesn’t dwell on the fact that the couple is female, even as she acknowledges that it might be unexpected (but no more so than anything else). This makes the book a great choice for any parents wanting to show their children various types of families, as well as for same-sex parents and our kids.

The wedding is definitively Jewish: there is a rabbi (a woman) and Jewish wedding traditions like reading the ketubah (wedding contract) and stepping on wine glasses. Publisher Joanna Sussman told me, “We were seeking great Jewish-themed stories featuring same-sex families that would be of interest not just to the LGBTQ community, but to the community at large.”

LGBTQ-inclusive kids’ books are rare, and those that celebrate any kind of ethnic or religious identity are rarer still. A lack of specificity may give a story broad appeal—but it is also important for children to see in books the various intersecting parts of themselves (and others). Kudos to Keshet and Kar-Ben for helping to make this happen.

Kellen Anne Kaiser’s self-searching, funny, and occasionally bawdy Queerspawn in Love is not a children’s book, but rather a memoir of her first serious adult relationship. Kaiser is writing, she tells us at the start, to try and make sense of its demise.

Kaiser first met Lior Gold in their Berkeley Hebrew school class. He left to join the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) and they drifted apart until reconnecting years later, shortly after 9/11, when he was home on leave and Kaiser was home between semesters in college. Romance bloomed, and the two of them attempted to keep it alive after he returned to his unit. The problem was not just distance, but Kaiser’s own struggle to balance her “peacenik” upbringing and left-wing Zionist leanings with dating an IDF combat soldier. On top of this, particularly after Lior leaves the IDF and returns to California, was the challenge of navigating the different expectations that any two people have in a relationship, especially two young people figuring out what they want to do with their lives.

Kaiser’s four moms are a constant background presence: Nyna, her biological mom; Margery, Nyna’s former partner; Helen, Nyna’s best friend, who parented with them; and Kyree, Nyna’s spouse from the time Kaiser was five until she was 18. Kaiser shows us how her upbringing imbued her with certain values and cultural touchstones, both Jewish and queer, that she carries into later life. She knows what it feels like to be marginalized, for example, and to have to speak up to defend those she loves. And in trying to get Lior to open up about his feelings, she observes, “I was used to a much higher level of emotional expressiveness. Think constant processing. Total sharing. Think raised by lesbians.”

She shows us, too, how lessons from each of her moms helped her through her journey—and how the overall message they conveyed, of building their lives on their own terms, helped her find comfort and strength as she and Lior parted.

I wish she had explained a few terms that may be unfamiliar to non-Jewish readers (like “Shabbas goy,” a non- Jew who helps observant Jews on the Sabbath). This is a minor quibble, though, for a compelling book that illuminates the sometimes complex interactions of identity, family, and relationships.

No review of Jewish, LGBTQ family stories would be complete without a mention of Transparent, Amazon’s Emmy Award-winning series, which just started its third season. Most in the LGBTQ community know it as a story about a transgender woman and her family. But the Jewish Daily Forward also called it “the Jewiest show ever.” Josh Lambert at Tablet observed that “it makes sense that it’s a Jewish family at the center of this story” noting “Jews were crucial, ardent supporters of sexual science and minority rights throughout the 20th century … often because, being Jewish, they understood that persecution or prejudicial treatment of any minority is actually a threat against all of us.”

It seems no surprise, then, that we are seeing more stories centered on Jewish LGBTQ families. I hope we continue to see stories for all ages about the many different intersections of LGBTQ families, cultures, and religions.

Dana Rudolph is the founder and publisher of mombian.com, a GLAAD Media Award-winning blog and resource directory for LGBTQ parents.