By Eric Berger

Naomi Marmorstein loves reading the free Jewish books she gets from PJ Library to her 1-year-old son Jonah, whom she adopted last January.

Her only complaint: the characters don’t reflect her non-traditional “mom-kid” family, as she describes it. The Center City resident even contacted the national organization to request that it include more diversity in family structure, race and ethnicity in the books and music it sends at no charge to nearly 125,000 subscribers with young children across the country, including about 3,000 in the Philadelphia area.

“The more diversity in family structure that we see in books, the better for the broader community it is,” said Marmorstein, a professor of psychology at Rutgers University-Camden.

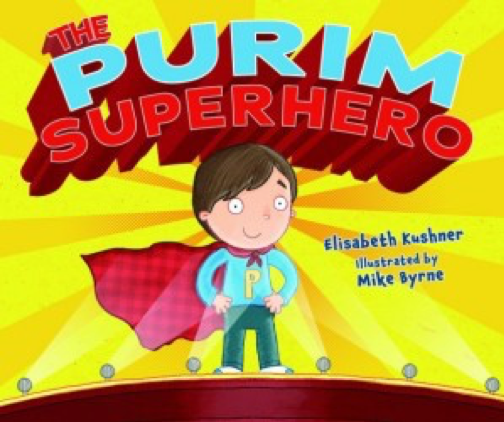

PJ Library pleased parents such as Marmorstein when it announced earlier this month that it would offer free copies of The Purim Superhero, a picture book by Elizabeth Kushner that tells the story of Nate, a boy with two dads who wants to wear an alien costume for Purim but feels pressured to dress up as a superhero like the rest of his classmates.

On Feb. 19, the organization announced that it was making the book available to anyone who requested it and quickly exhausted its supply of 2,200 copies.

The distribution earned praise from stakeholders such as Keshet, an LGBT Jewish advocacy organization that collaborated with Karp-Ben Publishing on the book. But Keshet also questioned why the nonprofit had not treated the book the same as its others, which are automatically sent to subscribers. (The organization is still offering the book but does not expect to have the additional copies available before Purim.)

PJ Library’s approach illustrated a fine line Jewish groups seek to navigate as they try to be more inclusive but also not alienate a particular segment of their constituency, in this case some Orthodox families who see homosexuality as a violation of Jewish law.

“We definitely see it as a compromise but also as an important first step,” Idit Klein, executive director of the Boston-based Keshet, said of the PJ Library’s decision. Keshet first lobbied PJ Library to include the book before Purim last year. “As an organization that works towards institutional change in the Jewish community, we are accustomed to seeing incremental successes and are familiar with the reality that generally one achieves progress on a small step-by-step basis.”

PJ Library director Marcie Greenfield Simon declined to comment, but pointed to a blog post by a trustee of the organization explaining that the organization must try to find a balance among parents with various beliefs.

“Parents have entrusted PJ Library to select age-appropriate books with Jewish content for their children,” the trustee, Winnie Sandler Grinspoon, wrote on the PJ Library’s website. “That sounds easy enough. But what about a book that some parents might welcome but others would not?”

“We think many families would love this book. Yet we know that there are some parents who would want to decide for themselves. And so, this month, we are putting parents in the driver’s seat,” she said.

PJ Library was founded by Massachusetts-based philanthropist Harold Grinspoon nine years ago with the hope that the books would lead to more conversations about Judaism among young families. Any Jewish families with children ages 6 months to 8 years old, regardless of need, can sign up to receive the free books in the mail. The project partners with local philanthropists and organizations, such as Jewish Learning Venture in Philadelphia, and recently started an initiative to distribute Arabic books to Israeli Arab preschoolers.

Amy Schwartz, director of the group’s Philadelphia program, said she has not yet heard any feedback, positive or negative, about Purim Superhero. But she made clear her own personal approval.

“I am a single parent household and for me it helps me reinforce the message to my kids that not all families look the same and it really helps my kids understand their own situation better by looking at other examples,” said Schwartz, who has three sons.

Klein pointed out that PJ Library subscribers may already receive books that don’t “resonate with their political or religious beliefs,” so she didn’t see why it should be taboo to include stories with characters that some may find controversial.

“For someone who didn’t want their kids to know that there were kids out there who have an Abba and a Daddy, or an Ima and a Mommy, of course that is their right as parents and it is their right to get that book and put it aside,” said Klein.

She also said that The Purim Superhero is “not a book about being gay,” but rather one that teaches broader lessons about “being yourself and claiming your identity.”

Lee Rosenfield, who lives with his husband and their two children in Lambertville, N.J., noted there is a dearth of literature, particularly Jewish books, that portray gay families. He said he had pushed hard for PJ Library to start distributing in his area and “sees it as a wonderful way to engage” young and unaffiliated families.

In offering the book by request rather than its usual distribution process, the organization, Rosenfield said, is “testing the waters.” But, he said, he thinks “it’s more offensive to offer the book as an elective that you have to separately go out of your way to request than it is to include it in your usual distribution. If someone receives it in the mail and says, ‘Oh my God, two dads, this is the most horrible thing — I don’t want to share it with my family,’ ” then they should just throw it away.”

Owa Zaga, an Orthodox mother of three in Elkins Park, said she reviews all the books from PJ Library to make sure they are appropriate and her children will like them.

“I think it is respectful” for PJ library to offer the book to those who request it, said Zaga, a preschool teacher at Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel. “I personally don’t have a problem with it, but I don’t expect everyone to be that way.”