By Irene Sege, Globe Staff

Tucked somewhere between the Scrabble Club and the Yiddish Club on the roster of 40 student organizations on the website of Gann Academy, the New Jewish High School of Greater Boston, is this listing for the group Open House: ‘’The gay-straight alliance at Gann Academy advocates for understanding and tolerance and provides a supportive space for discussion and learning.”

The straightforward description belies the soul-searching that challenged the Waltham school to put into practice its pluralistic ideal of serving Jews of all persuasions, from liberal Reform Jews to traditional Orthodox. The story of that process and of the round-faced girl who propelled it is presented in ‘’Hineini: Coming Out in a Jewish High School,” premiering Sunday as part of the Boston Jewish Film Festival. At a time when both religion and homosexuality are on the public mind, it examines how one community balanced its members’ profound and conflicting needs.

‘’Hineini” (pronounced hee-NAY-nee), Hebrew for ‘’here I am,” is an apt title for Irena Fayngold’s documentary. That, essentially, is what Shulamit Izen, then Gann’s only openly gay student, announced when she started her junior year in 2000 determined to found a gay-straight alliance. She’d just finished an internship with Keshet, the support and advocacy group for gay Jews that produced ‘’Hineini.”

‘’Struggling with Torah and with God is one thing,” Izen says on camera. ‘’What I don’t want to struggle with is my community.”

Izen, daughter of an engineer and a writer, grew up in Lexington in a Reform, staunchly Jewish home. ‘’We bought Jewish books but took secular books out of the library,” Izen, now 21, says in an interview at Brown University, where she is a junior. A bat mitzvah trip to Israel drew her to traditional Judaism. ‘’I came back,” she says, ‘’and said I feel I’ve been robbed of my heritage.”

She asked to attend a Jewish high school. Around the same time, four teachers had come out and Izen had spearheaded an all- school assembly. The Orthodox rabbi who heads the school was forced to wrestle with his sympathy for individuals’ quest for identity and his understanding of a Torah he considers the word of God that labels homosexuality an ‘’abomination.”

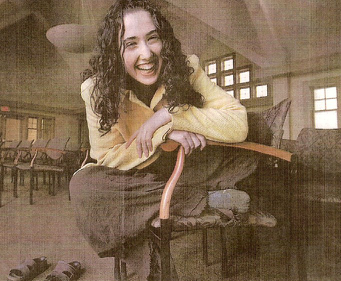

Shulamit Izen, now a junior at Brown University, founded a gay-straight alliance at Gann Academy, a Jewish high school in Waltham.

‘’It says in Genesis that we’re all created in God’s image,” Izen says on camera. ‘’but sometimes I feel like that doesn’t apply to the part of me that loves women.”

Izen pushed into the open an issue percolating below the surface. By the spring of 2001, two other Gann students and four teachers had come out and Izen had spearheaded an all- school assembly. The Orthodox rabbi who heads the school was forced to wrestle with his sympathy for individuals’ quest for identity and his understanding of a Torah he considers the word of God that labels homosexuality an ‘’abomination.”

‘’The core of our tradition is to bring together those conflicting opinions, not in an attempt to somehow resolve them or create harmony but to actually live in the tension of those differences,” the headmaster, Rabbi Daniel Lehmann, tells Fayngold. ‘’Shula,” he adds, ‘’challenged me to think about her as a person, not just an idea.”

Irena Fayngold’s documentary, “Hineini,” chronicles Izen’s efforts.

One school, many beliefs

Gann Academy, founded in 1997, is one of 22 Jewish community high schools in the country. Although Orthodox day schools continue to comprise the bulk of the country’s 759 Jewish schools, pluralistic schools, according to the Avi Chai Foundation, are the only non- Orthodox schools experiencing growth.

Gann educates 290 students in a light-filled, two-year-old building on 20 acres in Waltham. Forty percent of its students are Conservative Jews, 20 percent are Reform, 15 percent are Orthodox, and 25 percent fall outside these denominations. They range from those whose connection to Judaism is more cultural than religious, to those who believe the Torah is divinely inspired and subject to changing interpretation, to those who believe it is divinely written.

Fayngold, 33, captures this tension. ‘’Homosexual intercourse, as a sexual preference, is prohibited, and prohibited directly from the most fundamental sources of the Jewish tradition, from God’s own word,” Lehmann tells her. Susan Tanchel, the Bible teacher who came out the year Open House was formed, offers another perspective. ‘’Many things are quote-unquote clear in biblical texts that are no longer practiced. We don’t think about stoning a rebellious child. Deuteronomy 21 says take out your rebellious child and stone him,” she says. ‘’Why are some texts interpreted literally and others not?”

At Gann Academy, Shulamit Izen (above) realized her religious sensibility clased with her sexual identity. In her film, Irena Fayngold (below, with editor Michael Traub) explores that tension, as well as the disagreements among Jewish denominations.

Fayngold also captures the emotional stakes. ‘’It’s not just, ‘I’m gay; create a space where I can be gay,’ “ Ariel Wortzman, a lesbian student, tells her. ‘’Create a space where I can be open and talk about things that matter to me.”

An Orthodox student, Ari Shatz, expresses another viewpoint. ‘’I think what Shula wanted was for all Jews, all Orthodox, Conservative Jews, all Jews, to accept gay Jews. And I think that’s too much to ask because I think it’s wrong to be a gay Jew, and I think by asking that of me is in a way rejecting my belief and rejecting who I am,” he says. ‘’I still think it’s wrong to be Jewish and gay. But I’m not going to shun gay Jews, just like I don’t shun people for being Reform or for not keeping kosher.”

Open House limits its mission to education and support and tolerance, not promotion or celebration of a gay lifestyle. ‘’That’s a very difficult row to hoe,” says Brandeis University historian Jonathan Sarna, who chaired Gann’s religious practices committee. For the traditional Jews the pluralistic school seeks to attract to its mix, he adds, ‘’the idea of advocating a lifestyle that violates the Torah is unthinkable.”

Searching for acceptance

Public schools are required to establish gay-straight alliances upon students’ request. Private schools are not. The Maimonides School, an Orthodox day school in Brookline, doesn’t have a gay-straight alliance. Neither, according to an archdiocese spokesman, do parochial schools. Neither do the Lexington Christian Academy, the area’s largest Christian school, and the newer Boston Trinity Academy.

Among pluralistic Jewish schools, however, Gann is not unique. The upper school of the Charles E. Smith Jewish Day School in suburban Washington, for instance, has a gay-straight alliance. ‘’Given the growth of high schools such as Gann, coupled with the appearance of the film, it is very likely we will see the formation of more,” says Rabbi Joshua Elkin, director of the nonprofit Partnership for Excellence in Jewish Education and a Gann parent and board member.

Just as Gann struggled with the formation of Open House, so it struggled with the making of ‘’Hineini.” After Lehmann, in the spring of 2002, approved videotaping in the school, the board said no. Determined to proceed, Fayngold discovered images that student filmmaker Arnon Shorr had captured roaming the halls with his video camera. Initially, she felt ‘’this is a disaster,” she recalls, ‘’but the footage Arnon got I could never have gotten as an outsider.”

In early 2005, following ongoing conversations, Fayngold gained access to Gann’s visual archives, and Lehmann, after seeing edited clips, agreed to be interviewed. ‘’Because it was an independent film there were all sorts of questions about what kind of involvement the school should have,” Lehmann says by telephone from Israel, where he’s on sabbatical. ‘’I thought it was important, given the fact that the film was being done, that the school have some more official voice.”

Open House is not Gann’s only accommodation to pluralism. A liberal prayer group was formed after a student, a child of a mixed marriage whose father is Jewish, felt excluded from services that recognize only matrilineal descent. Sabbath retreats include one bunk for students who obey traditional prohibitions against work on Saturday — against using electricity or writing or driving — and another for less observant students.

Tanchel, now Gann’s associate head of school and Open House adviser, counts 10 to 15 active members but knows of no openly gay students. Last year’s ‘’day of silence,” aimed at drawing attention to anti-gay bias, attracted wide support. ‘’Students,” she says, ‘’know they have a place to come and to talk.”

Evolving viewpoint

Today, Izen, her curly hair piled loosely atop her head, majors in religion and dreams of becoming a rabbi and is modest about the events Fayngold chronicles. ‘’What my friends are doing in West Africa deserves a movie,” she says. ‘’It’s not something I think, ‘Oh, I’m so proud of myself,’ but I’m glad Open House exists. I learned a lot, and I’m glad I got to engage my school on a different level.”

Izen considers herself ‘’queer” now, not lesbian. ‘’I could be with either a man or a woman,” she says. She studied in Israel after Gann, then attended Smith College for two years. ‘’I was in a totally queer community,” she says. ‘’It was so not an issue that I could focus on other things.” She transferred to Brown seeking a broader Jewish community.

Fayngold shows Izen struggling with the feeling that ‘’to be Jewish and gay and holy,” as Izen says on camera, ‘’takes a little more than for straight people.” Izen’s thinking has since evolved.

‘’In high school I was ‘Torah is God’s word.’ Now I’m seeing it that way less and less. Now it really doesn’t matter how it began. It is,” Izen says. ‘’It says to welcome the stranger 36 times in the Torah. I don’t want to play that game any more,” she adds. ‘’In the movie I’m, ‘It says here this,’ and ‘It says here this.’ I became much more relaxed. I’ve been in a lot of safe places.”

Now, as then, she’s on a spiritual quest. ‘’I’m always thinking about what it means to be holy,” Izen says. ‘’How am I walking in the world? How am I letting people into my space? What tikkun— repair —am I doing? What chesed — lovingkindness? It’s gotten beyond sexuality.”

Sunday’s premiere of “Hineini” at the Museum of Fine Arts is sold out. It will be shown again on Nov. 19 at 7 p.m. at the MFA. Call 617-369-3770 or visit the MFA box office.

http://www.boston.com/news/education/higher/ articles/2005/11/08/minds_wide_open/