By Samuel G. Freedman

Nicole Bengiveno/The New York Times Anne Corey, left, and Connie Knapp found an unexpected obstacle in planning their wedding—finding clergy who would perform an interfaith ceremony.

OSSINING, N.Y. — One morning last summer, Connie Knapp got a phone call from her minister. Several days earlier, the Supreme Court had handed down a ruling fortifying the movement for same- sex marriage. Her pastor, the Rev. Chip Low, had a feeling that Ms. Knapp and her partner, Anne Corey, might want to have a wedding.

For going on 30 years, since they had met in a running club and fallen in love over spaghetti with clam sauce at a Chelsea diner, Ms. Knapp and Ms. Corey had considered themselves a couple. Yet even after gay marriage was allowed in New York State, they had vowed not to wed as long as the Defense of Marriage Act remained a federal law.

Now the high court had struck down a key part of the measure, which had denied federal benefits to married same-sex couples. After years of enduring opprobrium from religious conservatives, of being told that gays and lesbians were evil and immoral and intrinsically disordered and had provoked the Almighty to cause 9/11, the women had a friendly minister who had hung the rainbow flag outside his church and was offering to officiate at their ceremony.

There was just one obstacle. Ms. Knapp, born and raised Catholic, was now a Presbyterian studying for the ministry. Ms. Corey was from a Reform Jewish background. The women, both 65, were about to discover that in an era of growing acceptance of gay marriage, they would have no trouble finding clergy members ready to perform a same-sex ceremony. An interfaith ceremony, however, looked like a deal-breaker.

If the realization took them by surprise, Ms. Knapp and Ms. Corey were far from alone. As tolerance for same-sex marriage rapidly grows, interfaith gay couples are finding that the same spiritual leaders who support the civil right to wed might object on theological grounds to religiously mixed ceremonies.

“I have absolutely observed that increasing phenomenon over the years,” said Idit Klein, the executive director of Keshet, an advocacy organization for Jews who are lesbian, gay, bisexual or transgender. “I’ve seen it go from being difficult to find a rabbi to officiate at same-sex weddings to now having rabbis call me and say, ‘I’ve never done a gay wedding and I want to’ — a real eagerness to show solidarity. Something profound has shifted.”

“But what hasn’t shifted appreciably is most rabbis’ views of interfaith marriage,” Ms. Klein said.“Having interfaith families in their congregation is one thing, but officiating at the wedding is another.”

Keshet has a database of 713 rabbis or synagogues willing to perform same-sex weddings. Of those, however, Ms. Klein estimated, only about 20 percent are willing to hold interfaith ceremonies. Within the Reform Jewish movement, which has a decades-long record of supporting gay rights, only about half of its rabbis will conduct interfaith ceremonies, regardless of a couple’s sexual orientation.The Conservative movement’s rabbinical association has published guidelines for same-sexweddings, but prohibits its members from presiding at interfaith weddings.

The varying rules and norms within the rabbinate, in turn, put Christian clergy members in a reactive position. Among ministers willing to perform same-sex weddings, even within the faith, almost all are from the liberal mainline Protestant denominations.

At ground level, as couples like Ms. Knapp and Ms. Corey have discovered, fixed rules sometimes matter less than personal comfort levels. Some rabbis will marry an interfaith couple if the entire liturgy is Judaic; others, if the couple promise to raise their children as Jews. Some rabbis will co- officiate with non-Jewish clergy, while some will not. They may or may not accept the use of non- Jewish symbols and texts within the ceremony.

Mixing and matching heritages had seemed simple to Ms. Knapp and Ms. Corey for most of their decades together. They have held lesbian Seders annually since the mid-1980s, with their own cut-and-paste Haggadot. Ms. Corey goes to church with Ms. Knapp on Christmas and Easter. They read from a book of religious meditations each morning.

When Mr. Low came over last summer to start planning their wedding, the religious balancing act became trickier. Ms. Knapp, a college professor, yearned to be married in Mr. Low’s church, First Presbyterian in Yorktown Heights, where she was an active member. Ms. Corey’s self-described “bottom line” was that there be no reference to Jesus in the ceremony.

“When Chip came over and said, ‘Tell us about your family, about being Jewish,’ all of a sudden it felt important to me,” said Ms. Corey, a retired teacher. “I thought about my ancestors who came here to escape pogroms.”

Mr. Low contacted a local rabbi, Robert Weinerof Temple Beth Am in Yorktown Heights, to explore the possibility of jointly officiating. The rabbi had already performed several gay weddings,including one for an interfaith couple. But the spouses hadto commit to “creating a Jewish home” rather than “going down that dual-religion road,” he said in an interview.

For his part, Mr. Low felt marginalized by any ceremony that would avoid mentioning Jesus. “I get that it’s not easy for people of Jewish faith to hear how important Jesus is to Christians, how central,” he said in an interview last week. “And yet you need the ability of two faiths to be in dialogue and in tension with one another.”

Without hard feelings, but with a ticking clock, Ms. Knapp and Ms. Corey continued their clergy search. Through an organization of interfaith families, they were referred to a woman who described herself as a “rabbinic chaplain.” But, the couple recalled, she said she would not share duties with a minister.

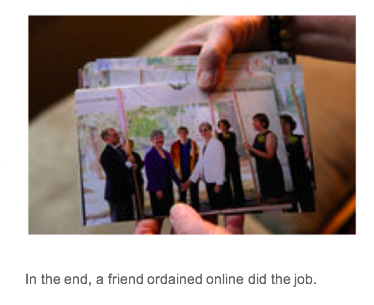

As their Oct. 13 wedding date neared, Ms. Knapp and Ms. Corey turned to a friend who was ordained online by the Universal Life Church. The ceremony, held at a conference center, included the chuppa, the Judaic wedding canopy, and the traditional breaking of the glass. The Sheva Brachot (seven blessings), though, drew from Apache and Buddhist sources, among others. In recognition of Ms. Knapp’s Irish heritage, one blessing was a Gaelic prayer.

In one respect, the difficulty of planning the wedding may have proved an important point for gay marriage supporters. “This is a really great demonstration of the religious freedoms that exist,” said Ross Murray, who runs the faith initiative for the advocacy group GLAAD. “People advocating marriage equality have kept saying that no one will force clergy to do same-sex ceremonies. The conundrum of interfaith couples shows that.”